The Dutch government is paying attention to the history of slavery. Our Prime Minister has declared 2023 the year of commemoration of the history of slavery. But the history of slavery goes beyond just transatlantic slavery and the abolition of slavery. However, colonial history is even more extensive, and includes various perspectives that continue to have an effect on the present.

An inclusive history

The colonial history of the Netherlands goes beyond the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Afro-Caribbean chapter. The extensive trans-Atlantic slave trade lasted until 1863. The colonial history, however, continued after that year under the leadership of the Dutch government and the Crown. The exploitation of the colonies continued unabated.

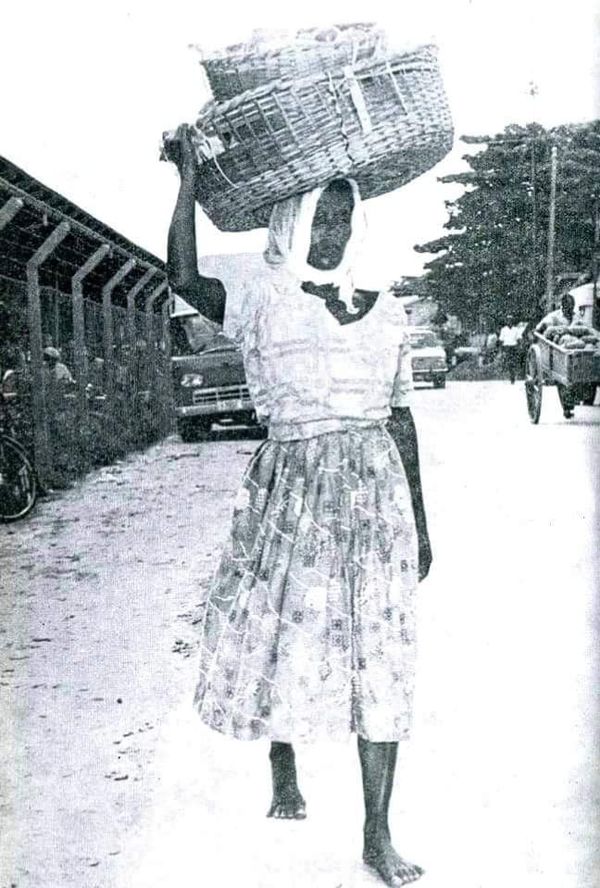

The shortage of cheap labor that arose after the abolition of slavery was supplemented by workers mainly from Asian countries. This supplement was more than necessary, as the prosperity of the plantation and factory owners – and thus of the Dutch State – could not decline. The recruitment of cheap labor from the aforementioned areas was accompanied by deception, lies, and crimes. This has resulted in a mixed population composition in terms of origin in the Dutch colonies. There were people from mainly (but not limited to) Indonesia (they were called Javanese, from former Dutch East Indies), from China, and from India (the Hindustanis from former British India).

The abolition of African slavery continued after its termination in other forms (of slavery). Even in the new system of slavery, the laborers were treated and exploited in the most horrific and inhumane way. There was a total destruction of humanity. Thus, the substitutes of the enslaved also suffered under this form of substitute slavery. Their cultural identity has also been gradually diminished by the plantation owners and the Dutch State, and they too have been systematically tortured and humiliated. And they too continue to experience the consequences of the deprived cultural values and identity by the former colonizer to this day. The consequences of the aforementioned destruction have irrevocably impacted the lives of the descendants. They too have been harmed, for which an account must also be given.

150 years ago

In 1863, slavery was administratively abolished in the Netherlands. But the actual freedom that came with it only took effect ten years later, in 1873. The enslaved people had to continue working under state supervision for another 10 years until the state found a solution for the loss of these free laborers. But that was not the end of slavery. In those ten years, people from various regions and different peoples were taken, with abduction not being shunned, to replace the workforce; Chinese (from 1858), Javanese (from 1890), and with the help of the British, Hindustanis.

In June 1873, the ship ‘Lalla Rookh’ docked in Paramaribo with the first British-Indian contract laborers to replace the enslaved people. In 2023, that will be 150 years ago. This moment is witnessed by a large group of descendants of the then “contract laborers” on whom the post-transatlantic chapter of colonial history began.

Historian Radjinder Bhagwanbali has conducted research on Hindustani history and has found extensive information in the Royal Archives about this new form of slavery, euphemistically called indentured labor, and the way the colonizers and planters treated their forced laborers. He has made shocking findings. He has laid this out in his book ‘Tot Koelie Gemaakten’. In the bibliography, there are references to his extensive lecture that you can follow about his research report on the Hindustani history within the national colonial history.

During her speech at Keti Koti 2022, Mayor Halsema said the following: “…This history has left a legacy in our city.” Grand and visible in the historic canal belt and the wealth of art. Much less visible—and long ignored—in the exploitation of the past and the inequality of the present. … Gradually, our historiography, with an eye on our legacy, is becoming more complete. …

But not only in the colonial territory of Suriname did the horrific substitute slavery take place; slavery also occurred in the East, particularly in the Dutch East Indies. Reggie Baay has written about this in his book ‘Daar werd wat gruwelijks verricht’. “… You cannot escape the conclusion that the Dutch, working for the much-lauded VOC, the flagship of Dutch trade, often displayed a sadism that was beyond comprehension.” For centuries. It will be one of the reasons why we hear so little about it, because it remains painfully silent when it comes to this part of our history. …” The president of Suriname, Santhoki, stated, “… that Rutte’s reason, as far as he is concerned, is the kickoff of a longer journey, which he himself describes as a ‘holistic process.’ In addition to formal Hague apologies for the entire slavery past, in fact, the entire colonial period should be scrutinized. We are talking about the Hindustani, Javanese, and Chinese migration. A lot happened during that period.” This also applies to the indigenous population of Suriname, the Amerindians.

In his speech of December 19, 2022, Prime Minister Rutte also demonstrates this awareness. ‘… Because centuries of oppression and exploitation continue to resonate in the here and now. In racist stereotypes. In discriminatory patterns of exclusion. In social inequality. And to break that, we must also face the past openly and honestly. A past that we share with other countries, which forever connects our societies in a special way. …”

King Willem III also spoke about this during his Christmas speech in 2022: ‘…by honestly confronting our slavery past and acknowledging the crime against humanity, we do lay a foundation for a shared future.’

At the same time, we are aware that we are still on the path to freedom when it comes to addressing the consequences of colonial history. We are at the beginning of this societal processing.

About the author

I am Aartie Mahesh and I am of Surinamese-Hindustani descent. My mother’s grandfather came from Agra (where the Taj Mahal is located) in British Guiana to work for a well-known British noble family. After returning to India, he decided to go to Suriname to make a living there. He settled in Nickerie and started his family there after his contract period.

An administrative remnant of this is that upon arrival in Suriname, his first and last name were registered as a double surname. Everyone in my mother’s family therefore carries his first and last name. The past is not far away. My great-aunt (daughter of my great-grandfather) is still around and talks about it. My own last name is the first name of my great-grandfather. In India, this is not a surname.

It pains me that this chapter of Dutch history is unknown and seems to be silenced. I want to raise awareness about our shared history so that we can approach each other with sensitivity. So that we can allow society to heal.