Dr. Chan Choenni

Introduction

Between 1873-1916 Hindostani indentured labourers arrived in Suriname. During 43 years these 30,304 Girmitiyas arrived often after a months-long journey with 64 transports from Calcutta (Kolkata) in India , More than a quarter returned after earning money in Suriname to India. Some 900 of them have returned again from India to Suriname after disappointing experiences in India. Letters were sent back and forth and money was also transferred from Suriname to their family in India. Till 1920, the term British-Indians (Brits Indiërs) was used by the Dutch colonial power for them because they were British subjects. In 1920 the national organisation of immigrants (SIV) decided to name this group and their descendants in Suriname Hindostanis. In 1927 they became Dutch subjects and in 1955 all Hindostanis acquired then the Dutch nationality. Nowadays, there are more than 350,000 Hindostanis residing in Suriname (150,000) and The Netherlands (180,000) and in small numbers in the USA, Belgium and The Netherlands Antillean islands. Many Hindostanis are searching mostly in vain for their roots in India. But, in January 2025 Premier Narendra Modi has promised to stimulate research in tracing their roots In India, There is indeed an urgent need for research of these roots. Research on regional level in areas where the recruitment took place is very important. For example, in the state of Bihar the areas Shahabad and Madhubani and the whereabouts of the subdepots in Patna and Muzaffarpur are key issues. Regional knowledge and networks are very useful. It is a history dating more than 100 years back. The first transport to Suriname was with the sailing ship Lalla Rookh in 1873. Lalla Rookh became an icon in Suriname.

We must keep in mind that there was also resistance in India against emigration of compatriots. Many emigrations left India covertly and in disguise using false names and changing their caste, religion or adding sing(h) after their name. Moreover, many did not have a surname or reported general names of cities and rivers like Mathura and Ganga. Sometimes names were written incorrectly or corrupted. Furthermore, a very negative image was often presented about indentured labour by the opponents of emigration.

Bharmai deis myth

The Girmitiyas themselves were often ashamed that they left their beloved land (janmabhumi) India. Many did not talk about their emigration and hardships. They did not pass information to their descendants. Others in Suriname rationalised their emigration using the myth of inveiglement (bharmai deis). For example, there is a myth that most Hindostani indentured labourers were misled. It was stated that most were allegedly recruited under false pretexts and misled by unlicensed recruiters (arkáthiyas). They were promised that they would end up in Suriname in paradise where they would eat from golden bowls and drink from golden cups. That is why thousands of Hindostani Girmitiyas are said to have emigrated to Suriname. There is even a song portraying this paradise.

Interestingly my research assistant asked one of the singers the truth behind this emigration. He admitted that there was abject poverty and hunger then in India. That was the true reason for emigration (see; Choenni 2016).This interview is recorded on film.

Another myth is the story about Sri Ram. The name Suriname/Surinaam was corrupted. Sri Ram/Sriram was the land (Desh means land) of the holy (Hindu Deity) Rama. SriRam Desh was said to resemble paradise where one would earn a lot of money and accumulate wealth. On January 13, 2025, Dutch television even showed a broadcast about the Hindostani immigration with the title False Paradise. It is a pity that the programme makers have not done a good research into the true reasons of the Hindostani emigration. They have thus painted a false picture of Hindustani emigration.

Some questions arise. Were the stories about paradise and SriRam Desh not unmasked during this long period of 43 years in which Hindostani immigration took place? If the story about golden bowls/cups were true, it could be verified during all these years? Were the Dutch planters so rich that they offered Girmitiyas food in golden bowls? Were the thousands of Hindostani so naïve to believe these stories? And the story about Sri Ram Desh did not apply to the other colonies where thousands have migrated? Was there no exchange of information about indentured labour in India, including in the recruitment areas in India? Didn’t the returnees tell anything in India?

The answer is that some arkáthiyas have made these false promises to some Hindostani. The story of deception – bharmai deis – was told over and over again. It could be used as a rationalization for the emigration from their beloved homeland. You could then say that you had left the beloved homeland (India) because you had been deceived. There are some anecdotal examples of deception and sometimes kidnapping by unlicensed recruiters. However, legal recruiters had to renew their license every year and when deception was found, their license was not renewed. Moreover, Indian emigration laws were strict and they were tightened to prevent such malpractices. It should be clear that the vast majority of Hindustani Girmitiyas have not been misled!

Premium

In the first phase of recruitment, some unlicensed recruiters have told these stories in order to lure Hindustani Girmitiyas into collecting a reward (a so-called bonus) themselves. These unlicensed recruiters delivered the recruited (potential emigrant) to the legal recruiter at the subdepot; for example, in Muzafferpur or Patna in the State Bihar. When the potential emigrant decided to emigrate after seeing the amenities included housing, free clothing, and food.in the subdepot in the various cities of the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, many agreed to emigrate. The arkáthiyas then received their premium. After receiving correct information about the payment in the colony for five year and after passing, a medical examination, the provisional employment contract with the Dutch government was signed. The Dutch government would not invest so much money (300 guilders; around 400 rupees then) if the recruited person did not agree to emigrate to Suriname, Then a group of recruits were taken by train guided by a Chaprassi to the port city of Calcutta. After a medical examination they were allowed to the Suriname depot and seasoned for the long passage. Then the sea voyage to Suriname commenced after a medical inspection. During this long procedure one third of the more than 52, 000 selected were rejected an in total almost 34,000 made the passage to Suriname. Evey emigrant received an emigration pass with important data.

The emigration to Suriname started in a later period (after 1873) compared to other colonies. Many had already migrated to Mauritius (after 1833), Guyana (after 1838) and Trinidad (after 1845). Hence, there was information available about indentured labour in the colonies for the Hindostani Girmitiyas. As said, there was also false information by the opponents of this emigration such as zamindars. For example, it was stated that there was harsh oppression, gross exploitation and forced conversion to Christianity. Furthermore, they would not survive the long sea voyage (the so-called kála pani myth) and women would be forced into prostitution in the colonies. i.c. Suriname. It was also claimed that oil was sucked out of the heads of the indentured labourers (mimiái ke tel). Nevertheless, many Indians choose to emigrate, because they heard also the true stories about the colonies from returnees. From Suriname the Hindostani chief interpreter Sitalpersad Doobay went to India to provide correct information. In 1913 many wanted to emigrate with him to Suriname. Afterwards some emigrants succeeded in passing all three medical tests and emigrated to Suriname. All in all, only the strong and brave did emigrate.

Push and pull factors

Hence, the overwhelming majority of Hindostani Girmitiyas have not been misled, but have knowingly emigrated to Suriname. After all, there were many reasons to emigrate from the then poverty stricken and colonized India. These are clustered into so-called push and pull factors. Push factors included poverty, unemployment, caste discrimination, storms and floods, famine, oppression of women, oppression of widows, family quarrels, a thirst for adventure and the chance to have a better life. Pull factors included the very high daily wage for Girmitiyas in Suriname compared to the daily wage in India. Furthermore, all transport, clothing, food and housing were paid for and the fact that after five years one could return to India for free with saved money. More than a quarter of the 34,304 Hindustani Girmitiyas returned to India with almost 200 guilders (on average) and value in jewellery. It was calculated that about half of the amount earned could be saved. Hindostani Girmitiyas have saved most of their wages during their contract period of five or ten years (recontract). The expression Phet kat kat ( to cut back on food) is well-known. Many regretted returning to India and wanted to return to Suriname. Only a small proportion succeeded, because they had to pass the medical tests again. Many Hindostani Girmitiyas and especially young men have secretly fled from India. Often, they have taken false names in order not to be traced by their family they had left. Many belonging to the highest caste (Brahmins) have also given up a false name and caste in order to be allowed to emigrate. Brahmins were not actually recruited.

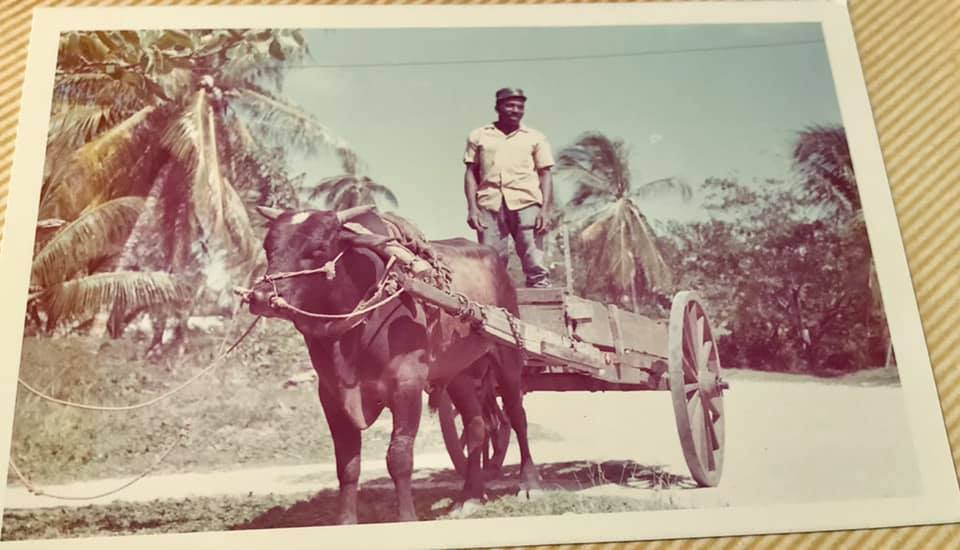

Government settlement places

Most Hindostani Girmitiyas acquired indeed a better life in Suriname .Surely, some have failed while others had a bad experience. But these are individual cases and must not be generalized to the total group. The fact that the large majority choose to settle in Suriname proves that they had a better life and a future for themselves and their children in Suriname than in India. Hindostanis belonging to the so-called lower castes in particular (about 40%) reached positions that were unthinkable in India at the time. Widows and rejected women could remarry and start families. There was mixing between castes because of the shortage of women and reciprocal marriages between Hindus and Muslims. Once in Suriname, most Hindostani people have seized the opportunities in this fertile land. The Dutch government wanted to keep the Hindostani people for Suriname. After 1895 they were given domain land of 1.5 to 2 hectares free of rent for 6 years and also the 100 guilder return premium. So much land under their own management was unthinkable for them in India at the time. In addition, many were given ownership of wild land and others even received free land from planters. Reclaimed land in the district of Nickerie was made available to them. In addition, so-called Government settlement places were set up. such as Alkmaar, Domburg, Laarwijk, Livorno, Meerzorg, Kroonenburg and Kasabaholo where they settled and became small farmers. Also, canals were digged on fertile land (Kandál) and boiti’s (side streets of Path of Wanica/Indira Gandhi Road) were established settling Hindostani families. After the indentureship period the Hindostani Girmitiyas settled in these regions and later in the capital Paramaribo. In due time they became successful through hard work, thrift and their drive towards advancement. The economic ethos guaranteed that their descendants became a successful ethnic group retaining their culture. There was an enormous population growth and in 1965 they became the largest group in Suriname.

No new slavery

All in all, the Hindostani Girmitiyas have toiled and been exploited on the Surinamese plantations. However, after five years they were free (khula). Assaults occurred during the indentured period, but sentences were imposed only after a ruling by the so-called circumventing judges. Prison sentences were imposed for refusal to work and fleeing from the plantation (desertion). After all, it was non-compliance with the obligations in the employment contract they had signed in India. On the basis of the so-called penal sanction, they were punished. For prisoners who tried to escape from prison, chains were used in prison. In 1891, certain planters wanted to reintroduce corporal punishment (whipping/catting), but this was refused by the then governor Savornin Lohman. However, these punishments during the Hindostani indentured period cannot be compared to the cruel punishments during slavery in Suriname. The claim that during the indentureship period it were the same planters and the same plantations as during slavery in Suriname is not entirely correct. Many planters had already left before and after the abolition of slavery. There were new plantation owners and other supervisors. For example, the large sugar plantation and the Marienburg company were only founded in 1882. More than a fifth of the Hindostani people have worked there. Marienburg used to be a small coffee plantation. Rubber (balata plantations), such as in Slootwijk or banana plantations such as in Kroonenburg where Hindostani Girmitiyas worked, also date from the period after slavery. And the large Waterloo sugar plantation in the western Nickerie district dates from 1845. A relatively small number of enslaved people worked there and later many Hindostani Girmitiyas. This means that indentured labour in Suriname cannot be compared to slavery in Suriname. Hence, this comparison with slavery is largely flawed. Most Girmitiyas were looking for a better life outside India. Most of them in Suriname had agency and succeeded after a harsh period in their ambitions.

Dr. Chan(dersen) Choenni is professor emeritus and was awarded the title of Knight in the Order of Orange-Nassau for his merits. He was born in Paramaribo in 1953 and is a fourth generation Indian. Chan Choenni has published seven books and numerous articles about the Hindostani history. His book History of Hindostanis 1873-2023; India. Suriname. The Netherlands will be released in May 2025.