© All rights reserved.

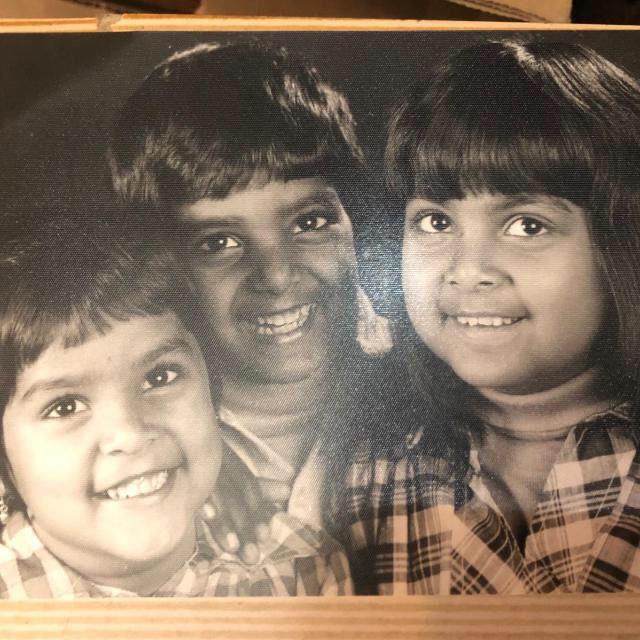

Shardhanand Harinandan Singh, Rotterdam.

Introduction

The European Convention on the Inapplicability of Limitation Periods for Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes, signed in Strasbourg on January 25, 1974, asserts a powerful principle: crimes against humanity are never time-barred. This includes the atrocities committed against Indian indentured laborers during the colonial era, spanning from 1833 to 1920. The crimes perpetrated during this dark chapter of history remain open for justice.

This column begins with a critical examination of how restorative justice can be pursued for the British-Indian indentured labourers who suffered at the hands of plantation owners in British, French, and Dutch colonies. It’s high time these crimes are brought to light, and those responsible held accountable.

Research into the history of Indian contract workers reveals a heartbreaking truth—no meaningful steps have been taken to rehabilitate the victims, or their descendants, even today. The indentured system placed Indian workers in appalling conditions, stripping them of their dignity, reducing them to mere commodities. The brutality faced by these workers closely mirrored the horrific experiences of enslaved Africans trafficked across the seas. In fact, just two years ago, the University of Glasgow launched a program focused on restorative justice for victims of human trafficking from Africa (Carrel, August 23, 2019).

As India continues to rise on the global stage, led by its dynamic PM Modi, it’s crucial that restorative justice for Indian indentured workers be brought into the international spotlight. The descendants of the oppressed, through their resilience and spiritual strength, have risen above their colonial past and now wield significant influence in the world.

Purpose of the Argument

This column advocates for a focused Indian mission to formulate and implement restorative justice for the indentured servants who endured unspeakable hardships under colonial rule. The exploitation of more than 1.5 million Indians, many of whom were shipped across the Kalapani to replace African slaves, needs to be addressed.

After the abolition of slavery in Western European colonies, more than 1.5 million Indians, primarily from northern India, were forcibly relocated to serve as indentured laborers in distant colonies. This move was supposed to replace the lost African slave labor. Yet, despite formal agreements between British colonial authorities and various colonial governments, these contracts were systematically violated. By 1913, international investigations into emigration from India had been completed, leading to political actions in India to halt the system altogether. In 1917, G.K. Gokhale, a prominent Indian politician, even introduced a resolution in Parliament to put an end to this exploitative system (Choenni, 2021).

While the indentured workers’ plight was recognized by some, little to no reparative action has been taken to alleviate the suffering caused to them, their families, or their descendants. Recently, the Global Girmitya Community, led by figures like Rai, has called on current authorities in the British Empire to take responsibility for these historical crimes.

Abolition of African Slavery and the Rise of the Indian Indenture System

The abolition of African slavery in the various British, French, and Dutch colonies took place between 1833 and 1848, prompting the British to look to Indian citizens to fill the labor void. This shift marked the beginning of the Indian indenture system, which lasted until the early 20th century.

In 1826, the French government on the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean laid the groundwork for recruiting and transporting Indian laborers, which was formalized in several laws. By 1838, an investigation into the emigration system was underway, driven by reports of abuse within the system. From 1833 to 1917, more than 1.5 million Indians were shipped to various colonies to replace the labor force lost due to the abolition of slavery. These workers were often unaware of the horrific journey they would undertake, and conditions were no better than those faced by enslaved Africans.

In Suriname, for instance, after just one year of shipments, the emigration process was suspended due to breaches of contractual obligations. However, three years later, it resumed with no accountability for the violations (Choenni, 2021). To this day, the suffering endured by the Girmityas—both during the indenture period and in the years following—remains largely unaddressed.

The Indian Girmitya Diasporic Policy

The question arises: What has the Indian government done to support the rehabilitation of Girmityas and their descendants, both in India and abroad? Between 1833 and 1917, around 1.5 million individuals were forcibly relocated across the Kalapani, with many leaving their families behind in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar (Rai, 2022).

One significant aspect of India’s diasporic policy is the Pravási Bháratiya Divas (PBD), a biennial event held since 2003 to celebrate the contributions of the Indian diaspora to the nation’s development. The most recent PBD, held on January 10, 2020, saw India’s Foreign Minister, Subrahmanyam Jai Shankar, emphasize the importance of the emotional and physical ties the diaspora has maintained with India. He praised the diaspora for helping elevate India’s position on the global stage, with Indian-origin individuals achieving success across the world.

However, the question remains: to what extent does the Indian government address the specific interests of the Girmityan descendants, who were forcibly displaced, and their families who were left behind in India? While the Pravási Bháratiya Divas celebrates the diaspora’s economic contributions, it doesn’t seem to tackle the historical injustices faced by the Girmitya community.

India has designed several provisions to support its diaspora, including the NRI (Non-Resident Indian), PIO (Person of Indian Origin), and OCI (Overseas Citizen of India) schemes. However, these policies primarily serve to support economic migration and engagement, with little attention given to the historical legacy of indentured servitude and its lasting impact on the descendants of these workers.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Since 2003, India’s engagement with the global Girmitya community has been a work in progress, fostering relationships that focus largely on economic growth and development. However, the historical trauma caused by the indentured system remains largely ignored. It is imperative that India’s policy evolve to include restorative justice for the descendants of indentured laborers, whose ancestors were subjected to brutal conditions and exploitation during the colonial era.

I urge Indian leaders and scholars, particularly within the diaspora, to take responsibility for confronting this painful chapter in history. This issue should not remain buried—justice must be pursued. I call on the heads of state in Europe to join India in acknowledging the injustice of this past and to work together to ensure that the suffering of the Girmityas is finally addressed.

Notes on Contributor

Shardhanand Harinandan Singh is a columnist, essayist, political analyst, retired change psychologist, and social educator. Recently, he has been deeply involved in Global Girmitya Community studies. He is a descendant of the fifth generation of indentured laborers who arrived in Suriname in 1895. After completing his teacher training in Paramaribo, Singh moved to Rotterdam in 1967. He later completed studies in social pedagogy and change psychology at the University of Leiden. In 1976, he co-founded the national welfare foundation Lalla Rookh, advocating for the interests of Sarnami Hindustani in the Netherlands. He remains committed to the Upanishadic philosophy of ‘Ekam Sat Vipra Bahudha Vadanti’—Unity in Diversity—as a guiding principle for integrating diaspora communities into the wider society.